The Proper London Guide

About the East End…

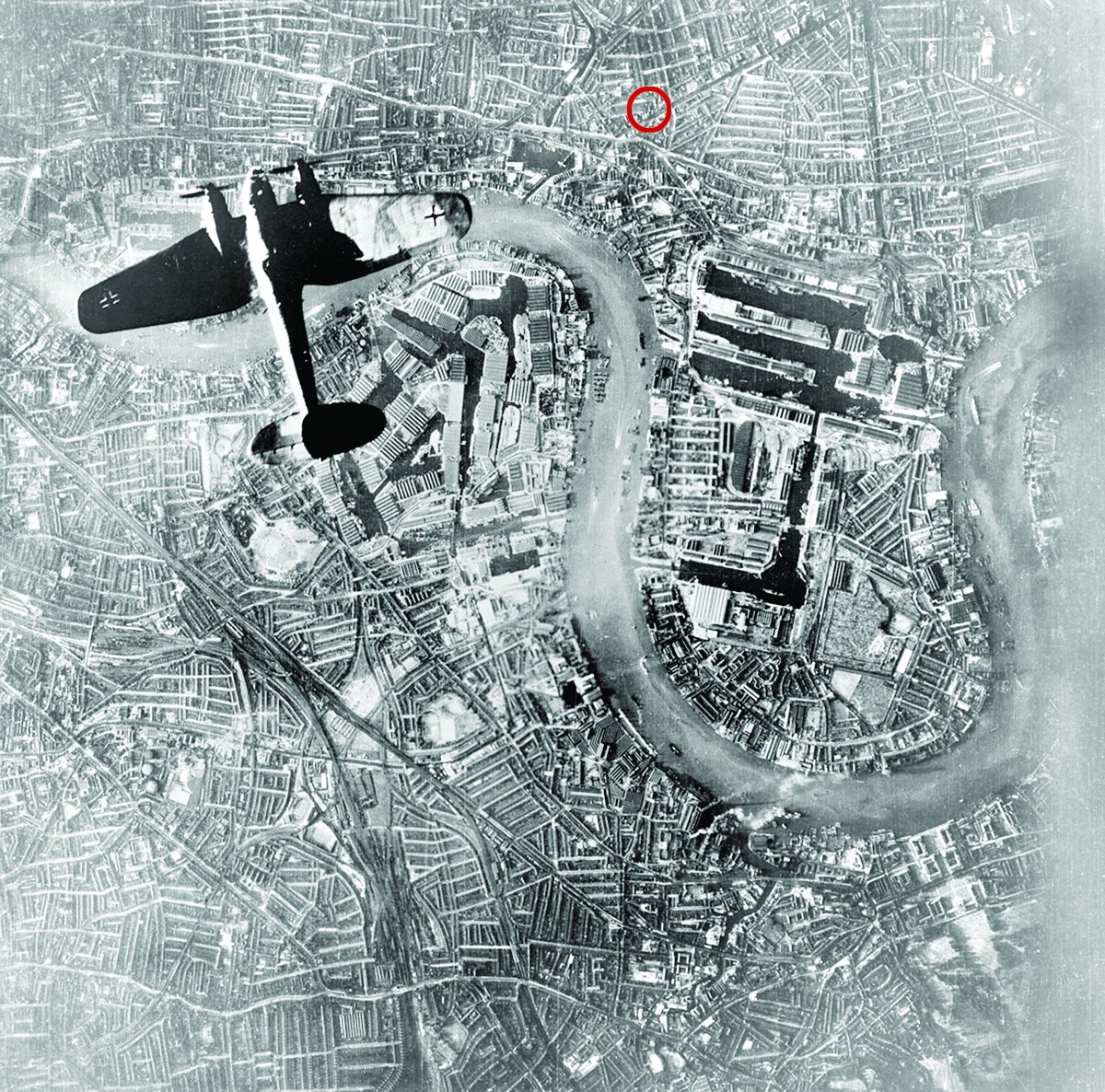

First of all, let’s get you orientated; the flat is on Copenhagen Place, London E14 7DX. It’s a new building (built 2003) on the site of a timber yard and warehouse that was blown to smithereens by the Germans during the Blitz of World War Two (October 1940 & June 1941). Over one year eight high explosive bombs fell on this site and the neighbouring warehouses. To this day there remain over 3000 unexploded bombs under the streets and buildings of London; at least once a year one is unexpectedly uncovered during the laying of new foundations or sometimes just rolling along the edges of the rivers that feed into the Thames. The all require the bomb squad to attend to carry out a controlled explosion. I’ve been evacuated twice in the East End while a WW2 bomb was being detonated in place. (Read the chapter on the Blitz in Peter Ackroyd’s “London. The Biography” it’s on the shelf).

East London is real London, by real, I mean the people that built the city and worked its viscera and organs. It was a slum and doesn’t forget that. Now let me tell you a little about each locale and former slum: Shoreditch, Spitalfields, Whitechapel, Narrow Street (Limehouse/Poplar), Borough Market, Bermondsey Street.

The origins of London slums date back to the mid-eighteenth century, when the population of London began to grow at an unprecedented rate. In the last decade of the nineteenth century, London's population expanded to four million, which spurred a high demand for cheap housing. London slums arose initially as a result of rapid population growth and industrialisation. They became notorious for overcrowded, unsanitary and squalid living conditions. Most well-off Victorians were ignorant or pretended to be ignorant of the subhuman slum life, and many, who heard about it, believed that the slums were the outcome of laziness, sin and vice of the lower classes. However, a number of socially conscious writers, social investigators, moral reformers, preachers and journalists, who sought solution to this urban malady in the second half of the nineteenth century, argued convincingly that the growth of slums was caused by poverty, unemployment, social exclusion and homelessness.

Latterly among them was Jack London, the American novelist.

Children sitting under a washing line in a slum area of Shoreditch London, 1889

Darkest London…

The most notorious slum areas were situated in East London, which was often called “darkest London,” a terra incognita for respectable citizens. However, slums also existed in other parts of London, e.g., St. Giles and Clerkenwell in central London, the Devil's Acre near Westminster Abbey, Jacob's Island in Bermondsey, on the south bank of the Thames River, and the Mint in Southwark. (All the areas of the map named “Proper London & Robbers.”) In the last decades of the Victorian era East London was inhabited predominantly by the working classes, which consisted of native English population, Irish immigrants, many of whom lived in extreme poverty, and immigrants from Central and Eastern Europe, mostly poor Russian, Polish and German Jews, who found shelter in great numbers in Whitechapel and the adjoining areas of St. George’s-in-the-East and Mile End.

“The People of the Abyss.”

Whitechapel: Whitechapel was the hub of the Victorian East End. By the end of the seventeenth century it was a relatively prosperous district. Whitechapel was the venue of murders committed in the late 1880s on several women by the anonymous serial killer, called Jack the Ripper, who possibly lived in the environs of Flower and Dean streets. The national press, which reported in great detail the Whitechapel murders, also revealed to the reading public the appalling deprivation and dire poverty of the East London slum dwellers. As a result, the London County Council tried to get rid of the worst slums by introducing several slum clearance programmes, but by the end of the nineteenth century few housing schemes for the poor were implemented. Jack London, who explored the living conditions of the poor in Whitechapel for six weeks in 1902, was astounded by the misery and overcrowding of the Whitechapel slums. He wrote a book about its miserable inhabitants, entitled “The People of the Abyss.”

Still want to visit?

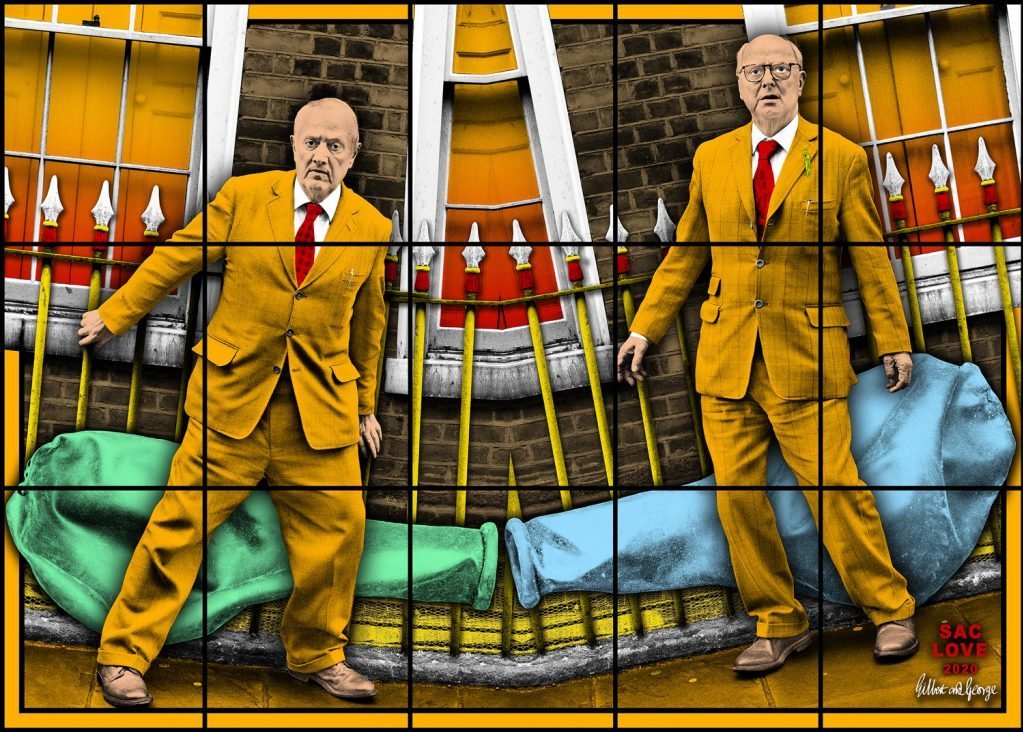

Spitalfields: In 1197 it was the home to The Priory of St. Mary of the Spittle, a medieval hospital. The first part of the name “Spitalfields” derives from the word “hospital,” which to the medieval mind was understood as “hospitality,” a place of rest as well as medicine. Spitalfields had been relatively rural until the Great Fire of London. By 1666, traders had begun operating beyond the city gates – on the site where today’s market stands. The landmark Truman’s Brewery opened in 1669 and in 1682, King Charles II granted John Balch a Royal Charter giving him the right to hold a market on Thursdays and Saturdays in or near Spital Square. The success of the market encouraged people to settle in the area; following the edict of Nantes in 1685, Huguenots fleeing France brought their silk weaving skills to Spitalfields. Their grand houses can still be seen around what is now the conservation area of Fournier Street. Today these houses are home to many artists including Gilbert & George.

Gilbert and George, SAC LOVE (2020)

Brick Lane ব্রিক লেন

The Huguenots were soon followed by Irish labourers in the mid-1700s escaping the potato famine, many of whom would work on the construction of the nearby London docks. As the area grew in popularity, Spitalfields became a parish in its own right in 1729 when Hawkesmoor's Christ Church was consecrated. The Irish were followed by East European Jews escaping the Polish pogroms and harsh conditions in Russia, as well as entrepreneurial Jews from the Netherlands. From the 1880s to 1970s Spitalfields was overwhelmingly Jewish and probably one of the largest Jewish communities in Europe with over 40 synagogues.

By the middle of the 20th century, the Jewish community had mostly moved on. Since the 1970s, a thriving Bangladeshi community has flourished in the area, bringing new cultures, trades and business to the area including the famous Brick Lane restaurant district.

Evidence of the people and communities that have given the area its unique character can still be seen – a Huguenot church, a Methodist chapel, a Jewish synagogue, and Muslim mosque stand among traditional and new shops, restaurants, markets and homes.

William Shakespeare came to Shoreditch as a young actor hoping to earn a living

Shoreditch.

The history of Shoreditch has been largely dictated by its location outside the City walls of London. The origin of the name is unknown, but it has a Saxon origin and may come from the “Sewerditch,” a stream that ran east of St Leonard’s church to nearby Holywell Lane. In the Middle Ages, the Augustinian Priory of St. John the Baptist in Haliwell dominated the eastern area. It was built near a sacred or holy well. The church was south of New Inn Yard. Holywell was founded by 1158, covered eight acres, and was the richest Augustinian nunnery in the country. The street pattern around the walls largely survives, being Shoreditch High Street, Holywell Lane, Curtain Road and Batemans Row. The priory site was split up at the dissolution of the monasteries in 1539. Several stone finds have been made. Curtain Road was named after the curtain wall there. At the north end of Shoreditch High Street was an ancient stone cross.

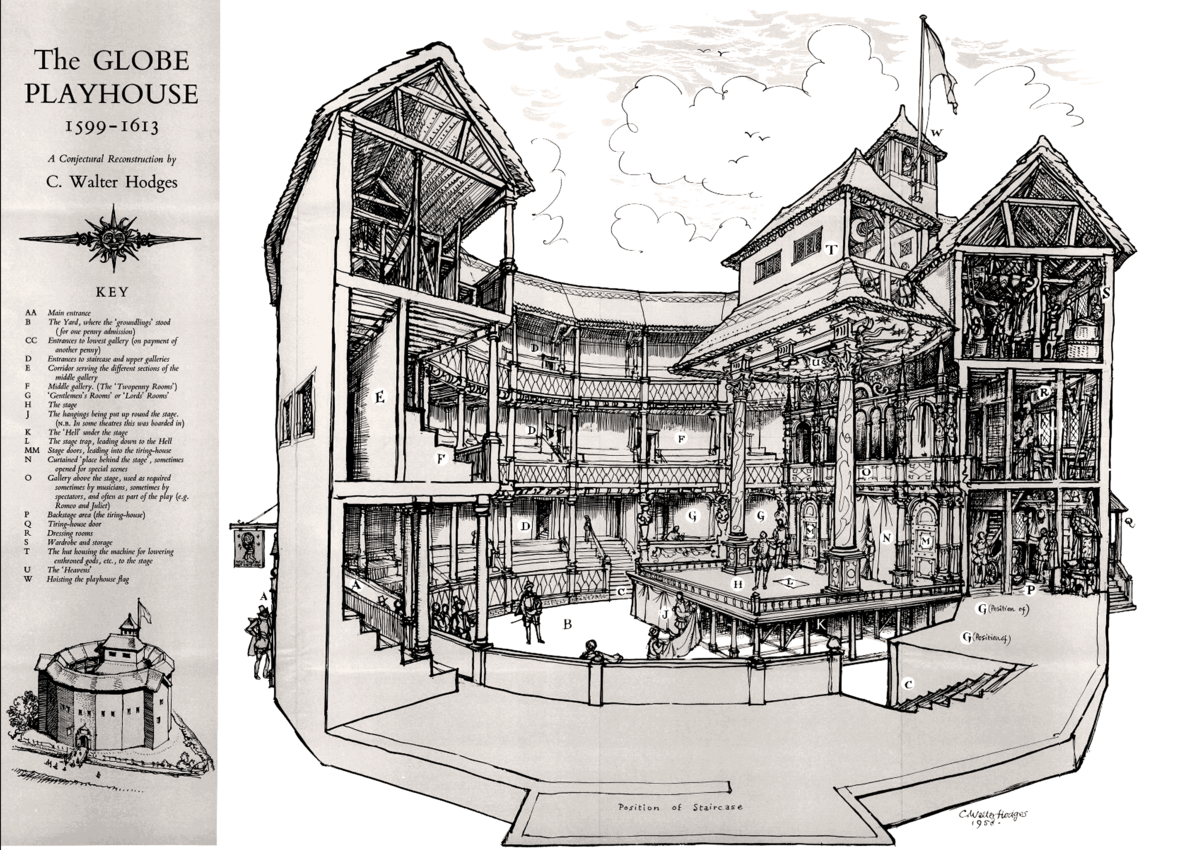

It is perhaps not widely known that the first two London theatres were built in Shoreditch. The first playhouse, called simply “The Theatre” of 1576 was on Curtain Road at the junction with New Inn Yard, the first permanent playhouse in Britain. William Shakespeare came to Shoreditch as a young actor seeking to earn a living; he lived in Bishopsgate and possibly also in Holywell Street, so far as records suggest.

James Burbage, the head of the Earl of Leicester’s Company of players, needed a permanent home for players to perform, as the Lord Mayor had prohibited plays from being performed within the City walls. Previously plays were held in places like inn yards or on the street.

In 2012 the well-preserved remains of Shakespeare's original “wooden O” stage of the Curtain Theatre were unearthed with new building works in a yard in east London. The Curtain Theatre in Shoreditch preceded the Globe on the Thames, showcasing several of Shakespeare's most famous plays; this is where “Henry V” and “Romeo and Juliet” were first performed. It was dismantled in the 17th century and its precise location lost. When the actor-manager James Burbage fell out with his landlord at the theatre, the company – according to cherished theatre legend – dismantled the timbers overnight and shipped them across the river to build his most famous theatre, the Globe, on Bankside (somewhere near the site of the contemporary Globe). The original site is now part of the gravelled yard in Shoreditch where groundlings (colloquialism for an unsophisticated spectator) stood, ate, gossiped and watched the plays. The foundation walls on which the tiers of wooden galleries were built have been uncovered in what was open ground for 500 years while the surrounding district became one of the most densely built in London.

Narrow Street (Limehouse/Poplar): The area of Limehouse was named after the lime kilns located at Limekiln Dock. Established by the 14th century when chalk was brought in from Kent to serve the London building industry, lime burning was the first of the “obnoxious industries” located downwind of the city. Between 1610 and 1710, the hamlet more than tripled in size, and by the early 18th century, it was absorbed by London’s eastern expansion. Limehouse became part of the industrial East End, notably and principally for its Chinatown centred on the Limehouse Causeway – and the opium dens that fuelled the more affluent of the slums

Borough Market in Southwark

This area lays claim to be the oldest of all the capital’s markets. Still trading on its original site, it celebrated its 1,000th anniversary in 2014. Borough, then as now, was a place defined by its position at one end of London Bridge – for centuries, the only route across the river into the capital.

It is likely that London’s first post-Roman bridge was constructed here in the mid-990s, partly to bolster the city’s defences against Viking raiders who routinely sailed up the Thames to kick seven shades of wattle and daub out of the locals. The bridge was later rebuilt in stone by Henry II and was itself a severe bottleneck, clogged with over a hundred shops and houses whose construction on the bridge had helped pay for it. The bridge was also home to London’s first public latrine. This is not the bridge you see today and would be a rather exposed latrine, not that that is much disincentive to a passing drunk City worker, with wads of cash in pocket. The proximity of the market, which sold grain, fruit, vegetables, fish and some livestock, accentuated the congestion problem, causing a serious impediment to the commercial life of the City. Almost three centuries passed until Edward VI granted a charter in 1550 conferring the market rights on the Lord Mayor and citizens of the City, who were thereby able to regulate the management of the market and the space it occupied. In 1671 Charles II issued a charter that fixed the limits of the market. This mapped it as extending from the southern end of London Bridge to St Margaret’s Hill, close to the present site of Guy’s Hospital, and to the former home, in today’s Talbot Yard, of the Tabard Inn from where Chaucer’s pilgrims set out for Canterbury.

Bermondsey Street (and the area of Bermondsey): Bermondsey takes its name from a Saxon landowner. It was originally known as Beormund's eg. The word eg meant an island, a promontory of land or, in this case, an “island” of dry land surrounded by marsh. (South London was marshy, which is why the Romans were reluctant to extend their fortification there. It is said that this became a cultural reluctance and is why to this day there is a bias against south London and why it has much less of the infrastructure the north does.) In the Middle Ages, a Cluniac abbey stood in the heart of the settlement. It was founded in 1089 by a merchant called Aylwin Child. Henry VIII closed it in the 16th century but its name lives on in the name Abbey Street.

A vast second-hand market grew on the site from the local trade from the then poverty-ridden surroundings. It remains a market today and is the site of some more unusual sales aided by a law that was passed in the 15th century. Known as the “thieves' charter,” the law allows criminals to sell or “fence” stolen antiques and art and avoid prosecution. People who buy stolen goods from a market overt (from the French Marché ouvert) between dawn and dusk acquire ownership or “good title” to the items. The international trade in stolen art has made good use of this legal loophole. Bermondsey antique and silver market, on Tower Bridge Road in South-east London, is the best-known market overt. The entire City of London area, which includes parts of Petticoat Lane market, is also protected. A trader at Bermondsey said: “'Crooks know which stalls to go to if they want to get rid of stuff. Everyone knows about the overt system, but I don't think many punters have any idea.”

Robbers, Tourists & Wankers.

In case you forgot, here’s a map.